Field Notes on Vanilla Javascript and Async/Await with XHR

I do Javascript as part of a raft of technologies I must use to get a number of tasks done, but most of where I use it, it could be turned off without the tools working.

Well, many, at least.

This leads me to be trailing-edge for a great number of JS styles and techniques.

So, I’ve been trying to pick up async/await.

Javascript is fundamentally asynchronous, so if there are three tasks — a, b, and c — and task b takes a long time, task c will jump ahead and finish first. This is a problem if task c relies on task b.

Async/Await is the newest method to put order onto a language that will route around it. First was Callbacks, which lead to “Callback Hell”.

(Yes, a demonstration would be good here, but I’m not here to talk about Callback Hell, and none of my tools have grown in such a way that this is their major malfunction. Yeah, there has been bad, but not this sort of bad.)

I am a patient boy / I wait, I wait, I wait, I wait

Following this was Promises. Metaphor Time: I ask for $20, saying I will pay you back. It will take time for me to get paid, hit the ATM, etc. There are two options: I will pay you back and you can use that money to buy lunch, or I’m a deadbeat and you drop me from your friend’s list.

function makeRequest(method, url) {

return new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

let xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.open(method, url);

xhr.onload = function() {

if (this.status >= 200 && this.status < 300) {

resolve(xhr.response);

} else {

reject({

status: this.status,

statusText: xhr.statusText

});

}

};

xhr.onerror = function() {

reject({

status: this.status,

statusText: xhr.statusText

});

};

xhr.send();

});

}

There are three parts of the Promise, as shown above:

- the return, which most languages have end the function, but now here. This allows the calling function to proceed, with the Promise function, which can

- reject, or throw an error and call me a deadbeat, or

- resolve, hand back the response content, or the $20 I owe you.

I’ve touched Promises, in JS and in Perl. The problem is that, in Perl, we know that tasks started as a, b, and c will end a, b, and c. The problem can be that we’re perfectly able to run c while b is blocking and it won’t. Perl Promises can help with that, but that isn’t the topic today.

Today’s Topic: Async/Await and Javascript as She is Wrote

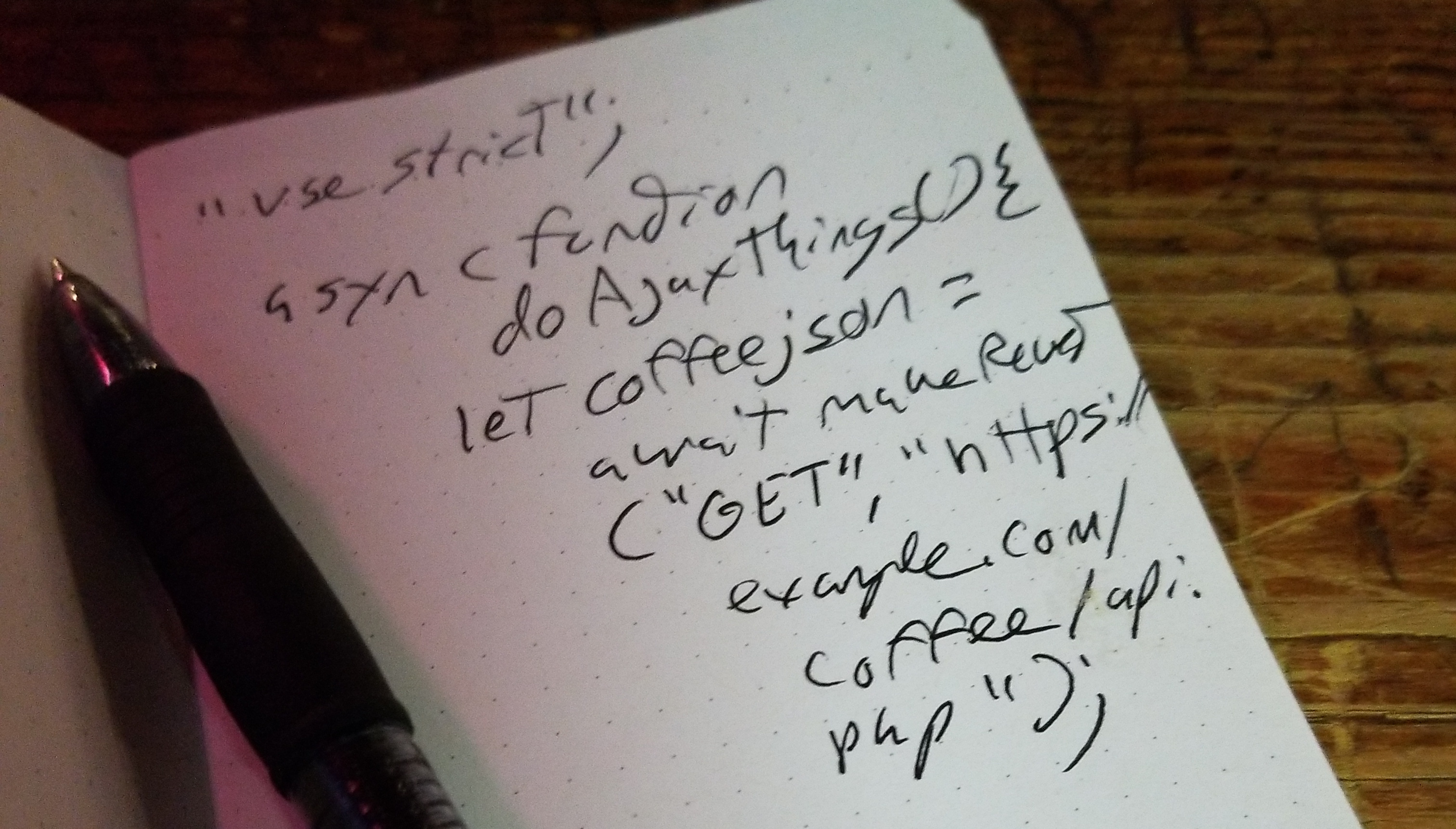

Different story here. It isn’t about me being a deadbeat. It’s about me being a Coffee Achiever. I cribbed a lot from Stack Overflow, especially this answer on using async with AJAX, which is exactly how I will use it and not often in the example code. I will break it into pieces and explain it as I understand it.

// my async javascript lib, which uses Handlebars.js

document.addEventListener("DOMContentLoaded", function() {

doAjaxThings();

// create and manipulate your DOM here. doAjaxThings() will run asynchronously and not block your DOM rendering

// document.createElement("...");

// document.getElementById("...").addEventListener(...);

});

This hits another long-lasting issue with JS: when do you run it? In the 90s, it was common to see the <script src="my_lib.js"> in the <head> with the <link rel="stylesheet" href="style.css">, but the problem was that the Javascript would trigger before the page was done loading, so it then became common to see it next to the ‘</body>’. The was “good enough” then, but we’ve become more insistent. In jQuery, the convention is

$(function() {

// this is the start of everything, called when everything is loaded

});

But I’m going vanilla in this post, and here, there’s an event triggered when all is ready, and that’s when the DOM content is loaded. So, "DOMContentLoaded", of course.

async function doAjaxThings() {

// get the coffee JSON

let coffeeurl = "//example.com/coffee/api.php";

let coffeejson = await makeRequest("GET", coffeeurl);

// get the template

let templateurl = "//example.com/templates/day.handlebars";

let template = await makeRequest("GET", templateurl);

let coffeeobj = JSON.parse(coffeejson); // we want it as an object

let week = coffeeobj.coffee.slice(0, 7); // just the last 7 days

// this creates a function that takes an object and returns HTML

let handlebar = Handlebars.compile(template);

// and where we're writing this

let coffeediv = document.getElementById("coffee");

for (let i in week) {

let day = week[i];

let html = handlebar(day);

coffeediv.innerHTML = coffeediv.innerHTML + html;

}

}

And lots of conventions in this. First of all, HTTPS Everywhere still has work to do, and so there are pages that are served without encryption. Within a page, if there is a part where anything is unencrypted, that is a point where bad stuff can get in, and there will be a problem. But, many times, the site is served in both https and http from the same document root, and the browsers allow //example.com to use the http(s) of the page as is. A clever thing that you might not have seen if you don’t do web.

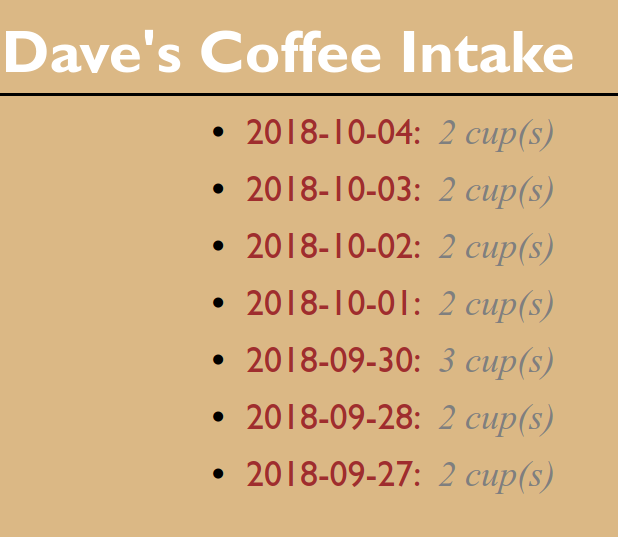

In this case, the coffee api returns JSON that looks like this:

{

"coffee": [

{ "date": "2018-10-04", "time": "1538659940", "cups": "2" },

{ "date": "2018-10-03", "time": "1538573881", "cups": "2" },

{ "date": "2018-10-02", "time": "1538487391", "cups": "2" },

{ "comment" : "YEARS OF COFFEE GO HERE" }

{ "date": "2012-11-14", "time": "1352920500", "cups": "2" },

{ "date": "2012-11-13", "time": "1352807940", "cups": "2" },

{ "date": "2012-11-12", "time": "1352752560", "cups": "4" }

]

}

My main remaining Quantified Self behavior. I mean, I still wear a FitBit, but…

It seems that the templating engine of choice for Javascript is now Handlebars.js, which was inspired by Mustache. This is because for both, if you wanted to put header in <h1> tags, the template would be <h1></h1>, and the curly braces look a lot like handlebar mustaches.

Our template puts the responses in <div> tags.

<div class="report">

<span class="date">:</span>

<span class="count"> cup(s) </span>

</div>

It seems like a good idea to put the moving parts in another function, but I haven’t yet. I think the “feed the day’s information into the function, get out HTML, add HTML to an element’s innerHTML” is fairly obvious. I could really imagine adding a setInterval to clear and rewrite the week’s count.

There’s a cheat here; you could easily put the template in the page instead of an external file. Depending on how much you change things, this could be perfectly acceptable:

<script id="coffee_template" type="text/x-handlebars-template">

<div class="report">

<span class="date">:</span>

<span class="count"> cup(s) </span>

</div>

</script>

But then, there would be little enough going on here that we wouldn’t need the Async. I can see the wonder being when you have a number of elements trying to work independently, and when these things build on each other. For example, in that above example, I might want coffeejson to update once every few minutes, but template might might change rarely once you have developed it.

If you have any questions or comments, I would be glad to hear it. Ask me on Twitter or make an issue on my blog repo.